Boulder to Burr Trail and The Circle Cliffs Uplift

Above, a Google Satellite view of Sugarloaf Butte in Boulder Town, alongside the beginning of the Burr Trail (the road at top left). Part of the western slope of the Circle Cliffs, this striking hill is predominantly Navajo Sandstone but is topped by layers of brownish to reddish-purple, gypsiferous (but quite hard) siltstone of the Carmel Formation of the Middle Jurassic period (ca 170mya, when seas again extended into this area).

The map below places the Burr Trail from Boulder to the Waterpocket Fold, and also helps us grasp what we are dealing with geologically.

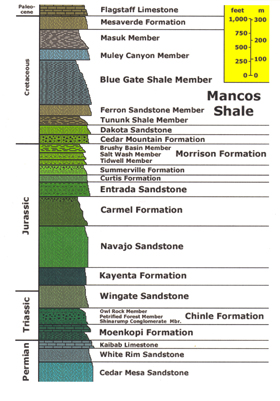

Click on the map if you want to enlarge it. As the map shows us, we have now moved well outside Capitol Reef National Park, and are traversing the "Escalante Canyons Section" of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. This Escalante Canyons Section can be subdivided into two landscapes based on physiography: to the west, and mostly out of our view here, the canyons and benchlands, and second the Circle Cliffs uplift, which is a large doubly plunging anticline, the core of which is eroded into a large kidney-shaped physiographic basin completely surrounded by imposing vertical cliffs of Wingate Sandstone. Our route carries us across the upper-central portion of this uplift, as you can see here on the map in red: "Burr Trail Road". But note that the uplift extends well beyond where you see the words "Circle Cliffs", further north and west all the way to Boulder Town vicinity and southwest to the Escalante River, which marks the southwest boundary of the anticline. The canyon labeled here above as "The Gulch" is part of this uplift.

Robert Steed wrote a landmark paper in 1954 on the Geology of Circle Cliffs anticline (See that link), identifying it as a substantial regional feature. [I am bound to point out, as a native son who grew up in Casper Wyoming, that at the time he was an agent scientist of the Ohio Oil Company in Casper.] As he says, Its length from north to south exceeds 60 miles, and its width between bounding synclines varies from approximately 8 to more than 30 miles. The eastern flank of Circle Cliffs anticline is coincident with the Waterpocket fold, one of the dominant structural elements in southern Utah, which extends over 80 miles from south of the Colorado River and northward into Thousand Lake Mountain. Circle Cliffs anticline is bounded on the west by the Kaiparowits downwarp, and on the east by the Henry Mountains downwarp. It plunges south across the Colorado River and is coaxial with a relatively small, northward plunging fold called Beaver anticline, which dies out on the northeast flank of Navajo Mountain dome. [For a more recent and much more detailed account of Circle Cliffs Geology, see this link: USGS Geological Survey Bulletin 1229.]

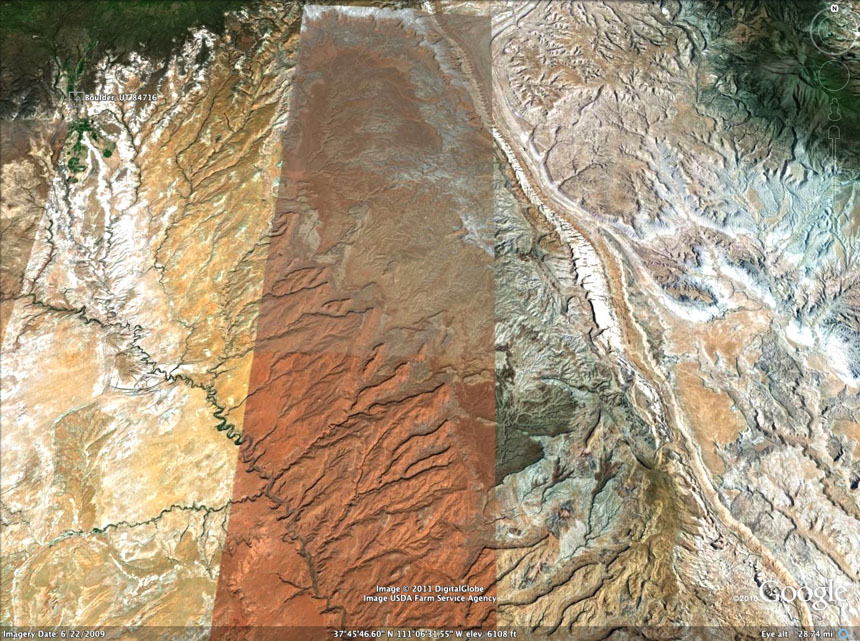

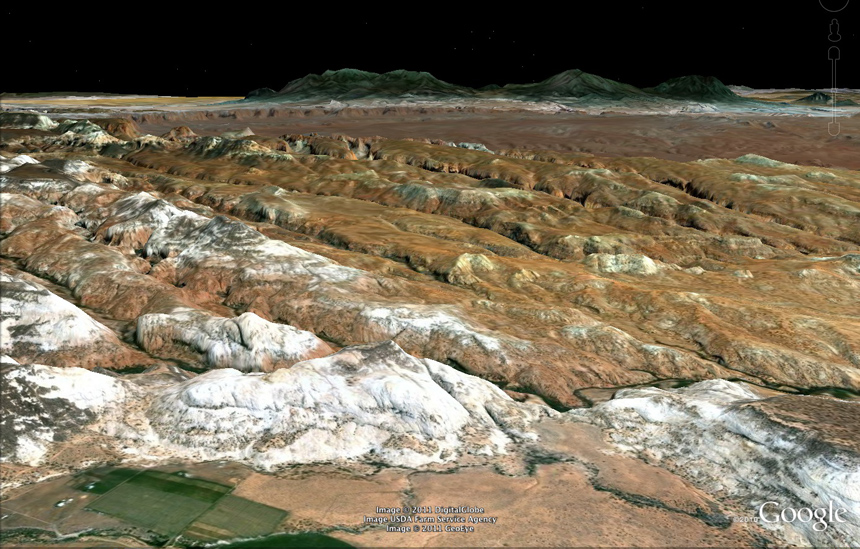

Below, this Google Satellite image shows the major part of the Circle Cliffs in our area (looking North), with its eastern margin, the Waterpocket Fold, running in a predominantly white line from top-center to lower right. The intensified redness of the middle vertical strip is to considerable extent an artifact of photography (as is the sharply yellowish imagery) , but there is in fact a color difference in the upper-middle portion of that strip, marking the geologically central dome of the Circle Cliffs Uplift. Remarkably, this dome-center is in part a depression in the anticline, due to the nature of the rocks in and around it and the way erosion has drained the dome into the Escalante Riover system. As Steed put it:

"The Circle Cliffs structure is a classic example of a breached anticline. Its central portion is marked by a long partially wooded topographic depression. Several scattered buttes and mesas rise more than 300 feet above the basin floor. Without exception, these remnants are capped by the Shinarump conglomerate [RNH: a hard, older Member of the Triassic Chinle] which is underlain by dark red sandstone and shale of the Moenkopi formation. The basin floor is marked by numerous deeply eroded canyons, along many of which the upper limestone member of the Kaibab formation supports a continuous bench. The central depression is completely surrounded by a high, vertical cliff of massive, red to buff Wingate sandstone. This Wingate escarpment is underlain by the delicately colored Chinle formation, which forms a steep slope. Beneath it is the 'inner escarpment', supported by Shinarump conglomerate." Shinarump is now considered by some to be a Member transitional between the lower, Moenkopi Formation and the higher Chinle, a ledge-forming, medium-to-coarse grained crossbedded sandstone and conglomerate.

The westerly portions of the Circle Cliffs show mainly in a more yellowish cast in the image above (though all these colors are in part distortions), represent later rocks and their erosion developed later. Note how the entire western body of the Circle Cliffs drains south and southwestward into the Escalante drainage which here runs southeastward (to end in the Colorado River at Lake Powell). Some small eastern drainages of the Circle Cliffs Uplift do flow into the Waterpocket Fold, as we shall see. And note of course also the white portions toward Boulder and southward, which are Navajo Formation exposures further west on the downward side of the anticline.

Below, while we don't go near a good Escalante River vantage point on this trip, it's convenient that Wikipedia provides this beautiful image of that river drainage from far downstream, looking upstream along a portion of the riverbed, with the Aquarius Plateau stretching across the horizon from west to east. Click on the image to enlarge it. Here too the river cut takes us down into much older rocks than the Navajo which blanket the field with white below the horizon. This is the general area addressed in my brief commentary on Why the CP Obsession?

Below, shortly into our Burr Trail travels toward the east, we encountered another remarkable example of deformed Navajo Sandstone. More will be said about its profound deformations in the subsequent section. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, I must admit we drove this part of the trail largely in ignorance, driving partly with an eye on the weather and not paying as much attention to geological formations. I would guess at what we were seeing here in this early portion of our Burr trip that the very highest buttes may be Navajo sandstone, the upper portion of the red cliffs in middle distance Kayenta Formation, and Wingate Formation the more orange-yellow strip below it. But that is merely a guess. We'll see these in detail shortly. Click on the image to enlarge it.

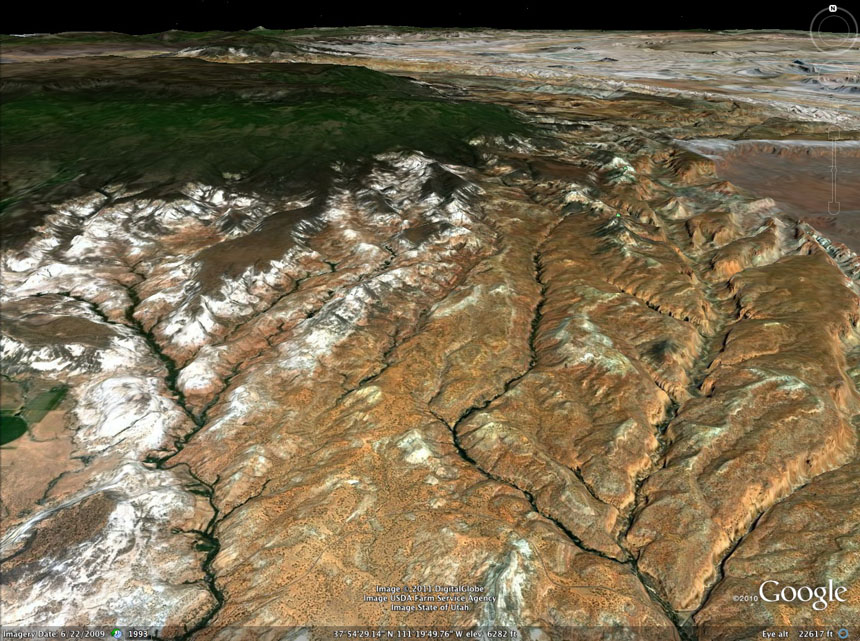

Below, Google Earth gives a 3-D Satellite view of this terrain from the perspective of Boulder Town at far lower right and looking east toward the Henry Mountains. These near terrains show scattered remnants of Navajo Formation toward the western side of the Circle Cliffs, with plateau strips exposing the earlier Kayenta Formation beneath Navajo, running roughly north to south toward the Escalante River.

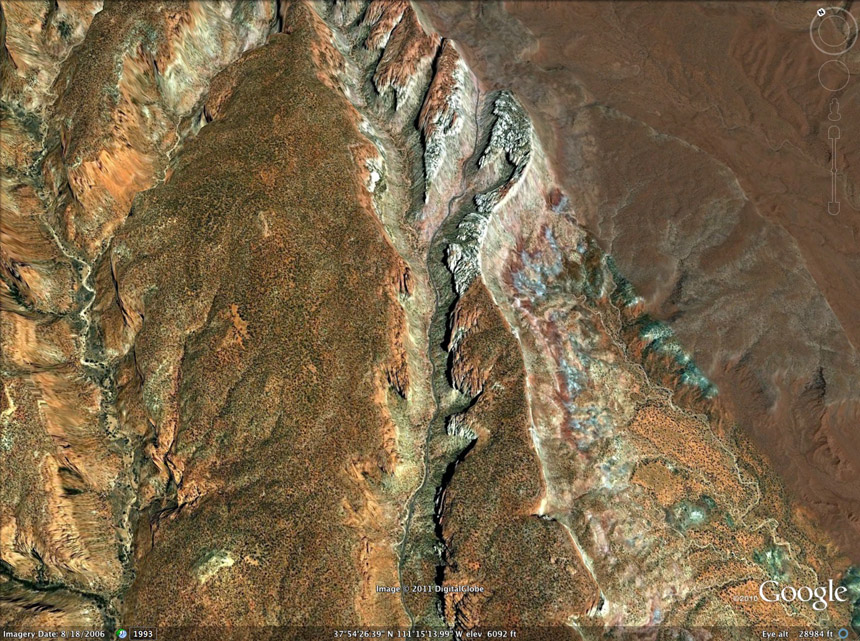

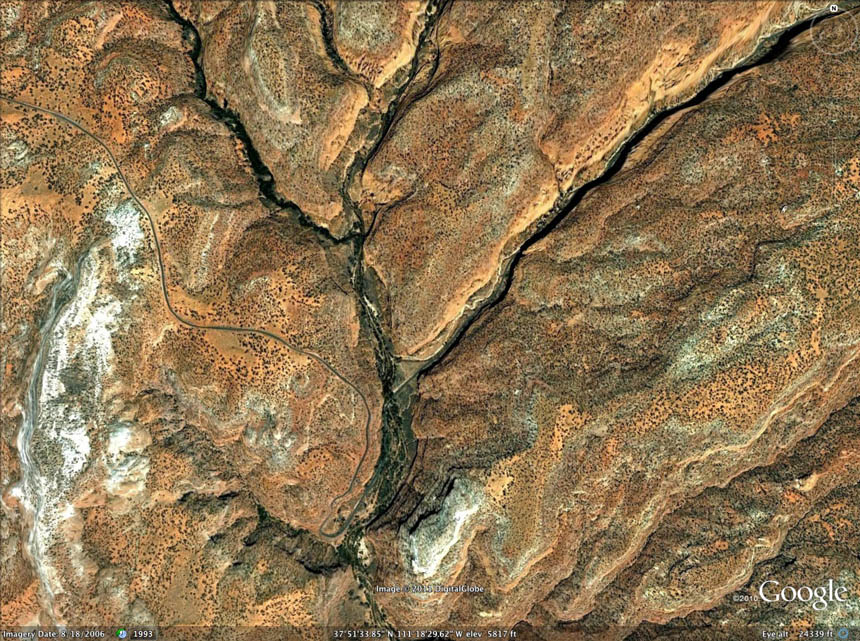

This Google image below sacrifices a strong 3-dimensional view in favor of a more straightforward north-south view of the route we traversed. You can see the route of the Burr Trail across the lower portion of the image. Click on the image to enlarge it. Note, in passing, the dark-purplish covering of the Navajo Formations on the lower flanks of Boulder Mountain toward upper left center. These are surely remnant Jurassic Carmel Formations (like those atop the Sugarloaf), but thicker in these locations. The main body of surface formation below is what appears here as orange (but this is partly due to conditions of photography): the Kayenta Formation with its interlayered red sandstone and siltstone. Toward the lower right corner and angling sharply northeastward to an edge, you can see our route destination at this point: to drop down into the Long Canyon. Note also more toward the center of this right-side dentritic system, the Gulch, which curves leftward away from the edge at the top. We will glance at it further below.

Below, the Burr Trail meets The Gulch, and the Long Canyon, which stretches to the far upper right at the top of this North-South image. You cen see below the middle where the road presents an overlook northeastward straight up the Long Canyon, where we will go. The Gulch forms the more-or-less straight-north branch of this dendritic system. Here's a link that takes you along the larger drainage system of which this is a part: The Gulch.

Below, we look from the promontory shown above and into Long Canyon (a view which in my 2000 travels helped fix the Obsession of which I keep speaking). Here we see the truer color (and gauge some of the thickness) of the Kayenta Formation. We of course entered its mysteries without further delay. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Even at a distance it appears as a dark-red, maroon, or lavender band made up of beds of sandstone, with minor amounts of sandy shale and thin limestone strata, all lenticular, uneven at their tops, and discontinuous within short distances. They suggest deposits made by shifting streams of fluctuating volume. Steed observed that the upper and lower contacts of the Kayenta are vague owing to intertonguing with the overlying Navajo and underlying Wingate sandstones. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, note the lenticular collapse of a wall portion, now stained with desert varnish, its old debris pile lying in eroded mini-domes below. Click on the image to enlarge it. This middle Member of the "Glen Canyon Group" Blakely et al, in their latest map, link to the Navajo as an Early Jurassic Colorado Plateau characterized by increasingly severe, regional dessication. See that link.

We saw "desert varnish" (see that link) forming exquisitely beautiful tapestries along the underhangs of the Kayenta all along this closely-confined passageway, as the image below attests. Click on the image for a closer view. This artistry is formed by collaboration of several kinds of bacteria with mineral dusts over periods of thousands of years, and its dating has become an important project for archaeologists since much Native American rock imagery was made by removing bits of it ("pecking") with a sharp stone.

Below, Proceeding northeastward up Long Canyon, we begin to encounter underlying layers of a much lighter and differently-structured Formation below the Kayenta. Google Earth shows us also a remnant outcrop of Navajo Formation topping the Kayenta at this location, far upper left. Note also the vertical fracturing of the formation at lower right-center. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, as we approach the end of Long Canyon, the underlying, lighter-colored Formation becomes more and more prominent as the darker reddish Kayenta pinches out above: Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, Google Earth's satellite image gives you some idea of the visual shock we experienced when the Canyon abruptly ends: here the view to the top is toward the northeast, and you can see the roadway leading out to the edge of the western escarpment. There, to the right of the road, Kayenta Formation has been completely eroded away leaving the lighter-colored Wingate Sandstone. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Here below we encountered another visually stunning point of view. Towering overhead, we observed a veritable Sphinx-bird of Wingate, whose backbones are Kayenta-red. Steed's description: "The Wingate is massive, cross-bedded, red to light buff, fine- to medium-grained quartz sandstone. It forms a vertical cliff that completely rings Circle Cliffs anticline." This formation is, like its later Glen Canyon co-Member the Navajo, predominently an eolian deposit, and is some 280 feet thick in places here. Though not as geographically extensive as the later Navajo, Wingate formed an erg over much of northeastern Arizona and central Utah, with sands that blew in from the Oachita-Appalachian Mountains complex (extending from central Texas far to the southeast).

This image also nicely shows how the Wingate lies directly and unconformably over the Triassic Chinle Formation, more on which in a moment. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below left, a closeup view of desert varnish running down the Wingate overhang shown at middle left above. Note the lines of deformation stress running laterally across the face. Here Helen Henderson and two friends admire it with rapt attention. Click on each image to enlarge it.

Since the Wingate Formation is so massive and distinctly aeolian, we wondered about an apparent ambiguity concerning its placement in the geological (and ecological) sequence. Wikipedia now says this: "Although traditionally thought to date to the Early Jurassic only, fossils (including a phytosaur skull) and other evidence indicate that part of the Wingate Sandstone is Late Triassic in age. The upper part of the formation, which laterally interfingers with the Moenave Formation to the west, is Early Jurassic in age." Adding to the complexity is the fact that the Najajo and Kayenta "interfinger" with the Wingate in some places, and both of these are also placed in some sequence constructions as transitional between Triassic and Jurassic in time. Since the Wingate is widespread in the Colorado Plateau, and particularly thick our area here, this surely suggests a considerable sand sea at that time.

At left, a closer view of the Chinle Formation which underlies the Wingate at this point.

Steed's description: Chinle strata are made up primarily of red, lavender, buff and green claystone, with nodular and cherty limestone in the upper portion. Sandstone and conglomerate occur near the base. Petrified wood is abundant in the lower portion of this formation. Silicified logs, up to 40 feet long and 3 feet in diameter, were observed immediately south of where Horse Canyon enters the outer escarpment on the west side of the Circle Cliffs.

Click on the image to enlarge it. You may want to do so in considering our brief description of Members here.

First, note at upper right the sharp unconformity between the base of the Wingate and the much darker and diffrerently-structured rock below. Steed's account would indicate that this is the Church Rock Member, the final deposit of the Chinle, composed of brown, massive, fine-to-medium grained sandstone, which here is found in very limited lenses no more than 25 fee thick. So it is here.

Below that runs a sequence of slopes and small ledges that marks the Owl Rock Member, composed of red, brown, and greenish-gray sandstone and mudstone, with occasional greenish-gray thin lenticular limestone beds.This is the array we see here running down to the road below the Church Rock Member, and it has thicknesses from 150 to 250 feet.

In the image below, now looking down below the base of the roadway, we see the Petrified Forest Member, the variegated bentonitic mudstone and sandstone with which we had become so familiar during our March 2010 Journey, which largely (but not intensively) surveyed the Petrified Forest, and therefore the Chinle. Lower down this same slope toward upper left, we may be seeing the earlier Monitor Butte Member , which has a more grayish-red bentonitic and gray to light brown sandstone. See This link from Blakely et al for their new map on the Chinle Petrified Forest Late Triassic. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, a closeup view of the rocks further down the slope from the Bentonitic shapes: these whitish cliffs and ledges may comprise the Shinarump Member, medium-grained thin to thick crossbedded sandstone; interbedded white thin-bedded sandstone and greenish-gray mudstone, and light-yellow very thick bedded sandstone. It contains carbonaceous and charcoaly material. This low to lowest Member of the Chinle forms a hard cap that protects the softer (and unconforming) layers of the Moenkopi Formation. This too is our guesswork, but the underlying rocks do have a definitely Moenkopi look. More on this point shortly.

Now we look out beyond the immediate zone across the entire northern expanse of the Circle cliffs, all the way across the uplift (now, paradoxically, something of a depression as we've already learned) toward (though so distant it's nearly out of view here) the same run of enclosing cliffs we stand in front of here. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, Google Earth shows us the route of the Burr Trail as it moves (lower-middle far left) out into the central, depressed portion of the Uplift. You can see the road swing northeast between two buttes, then it angles southeastward to the lower right until it crosses a small wash, then rises east-northeastward. Click on the image for a wider and larger view of the center of the uplift. The two buttes at upper left are topped by the Shinarup Member of the Chinle, here looking pale gray, which forms a discontinuous bluff (the inner escarpment) within the Circle Cliffs, part of which you can see below at far lower left. It is also the supporting cap on several buttes and benches within the enclosed basin.protects the softer, underlying and softer Moenkopi of the earlier Triassic (see Blakely et al new map for Early Triassic Moenkopi).

Below, this Google Earth image takes us into the center of the Uplift, where (I believe) most of the bright gray structures are Shinarup conglomerate capping the underrlying Moenkopi Formation. We encountered the muddy Moenkopi in our 2010 Petrified Forest Trip, where it characteristically displayed ripple marks indicating shoreline conditions. According to Blakely et al., this area was a Moenkopi Sea, though a very shallow one with vast playa-like margins surrounding it for many miles.

Everywhere here, the upper, softer portions of the Chinle Formation are long gone via erosion mainly into the Escalante River. The Burr Trail runs somewhat diagonally down through left center (right of the straight white streak) to the bottom of the image. Some of the canyons in this central zone cut way down through the Moenkopi Triassic Formation and into Permian Kaibab marine limestones and deeper. We "saw" none of this as we passed.

Below, our main image from driving the central portion of the uplift (the large cloud formation looming to the north over yet beyond Boulder Mountain was giving us cause for concern in light of recent very heavy rains) is this scene. Most striking is the view over the encircling cliffs to the central portion of Boulder Mountain, its flat volcanic top darkened by clouds but clearly visible to the norhwest.

In retrospective closeup view, the scene is more revealing. Below (enlarged and cropped), near dead center, an isolated remnant of Navajo Sandstone rises above the long cliff of Wingate Sandstone forming the main escarpment of the Circle Cliffs. At left center, the escarpment (now closer to us) still bears some of the darker-red Kayenta Formation standing above the more buff-colored Wingate. Well below that array, what Steed called "the inner escarpment", the Shinarump-Chinle capping the underlying Moenkopi, runs from dead left-center into the center of the image (above the shadowed flats). So we were riding here through some of the middle or perhaps even lower Moenkopi Formation. Note also the apparent tilt of these formations in thhe direction of their parallel erosion courses toward the southwest.

Eventually, looking toward the southeast below, the eastern boundaries of the Circle Cliffs Uplift came into clear view, standing here in much sharper inclination than their disposition on the western side. This is the Wingate Formation, our first good view of the top edge of the Waterpocket Fold downdrop. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, we turn to look back toward the northeast (and the mass of the Henry Mountains), and see another outcrop of the Wingate standing at the edge of the Fold.

Below, as we came closer, sharply tilted Wingate "flatirons" (here they look more like "chevrons", but their shape viewed from above looks much sharper; "flatirons" is the proper terminology for these hogback "teeth") stand out, contrasting with the underlying and softer Chinle at their bases closer to us. Behind the Wingate the younger (but impressively thick and massive) white Navajo sandstone marks the sharp edge of the Waterpocket Fold. Note that we are looking southwestward at this point, and the gently-upsloping flat, tree-studded formation lying apparently just beyond the Navajo is part of the Henry Basin, well across the fold but looking much closer in this telephoto image. In our substantial ignorance, we were unsure of what we were seeing at this point. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Again, here we could see the Glen Canyon Group cliff-edges in the mid-foreground, but were uncertain about the huge cliff formation in middle distance. This sloping plateau (with a low rise at far left, a stronger inclination toward the right) lies on the far side of the Waterpocket Fold, and comprises much later rocks than those we have been seeing, the relatively undeformed Cretacous rocks of the Henry Basin but now rising as a marginal part of the uplift. Coming from the inner Uplift onto this sudden panorama was disorienting at first. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, looking southeastward we drop into one of the small miniature valleys that drain to the east off the Uplift (instead of toward the south). Again, "flatirons" of the hard Wingate form cliffs above the older, much more gently sloping gray-and purplish Chinle Formation (and perhaps older rocks toward the base) that runs out toward us. This would be a good place to look for boundaries in these strata. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, we now enter among the chevrons of the Fold, and I think what we see here is likely Wingate at left, Kayenta in the middle, and (defintely) Navajo to the right. At far middle-left, you see the Uplift mini-valley we have just traversed, as we approach the narrow, steep switchback passwageway that was originally the sole meaning of "Burr Trail", that is, a route off the Uplift and down through the otherwise nearly impassible "Reef". Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, a closer view of the mini-valley, whose strata we didn't really observe as we crossed it.

And at last, below, we see clearly the expanse of the Waterpocket Fold, a vast two-sided valley opens out, lit by afternoon light: Click on the image to enlarge it.

and descend down into it along switchbacks framed by Navajo (upperleft) and Kayenta. Lower right; and Wingate? The Kayenta seems thinner in this location. Click on the image to enlarge it.

And here we stand on a thin strip of Kayenta and look out toward massive cliffs, mesas, and the basin of the Henry Mountains, confronting us across the wide valley of the Waterpocket Fold. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Click on the image at left to enlarge it!

Go to:

3d. Beyond the Waterpocket

or, go to other locales:

Return to Part One: Introduction

Go to Part Two: From Blanding to Capitol Reef

Go back to 3a. Boulder Mountain to Boulder Town