Boulder Mountain to Boulder Town and Vicinity

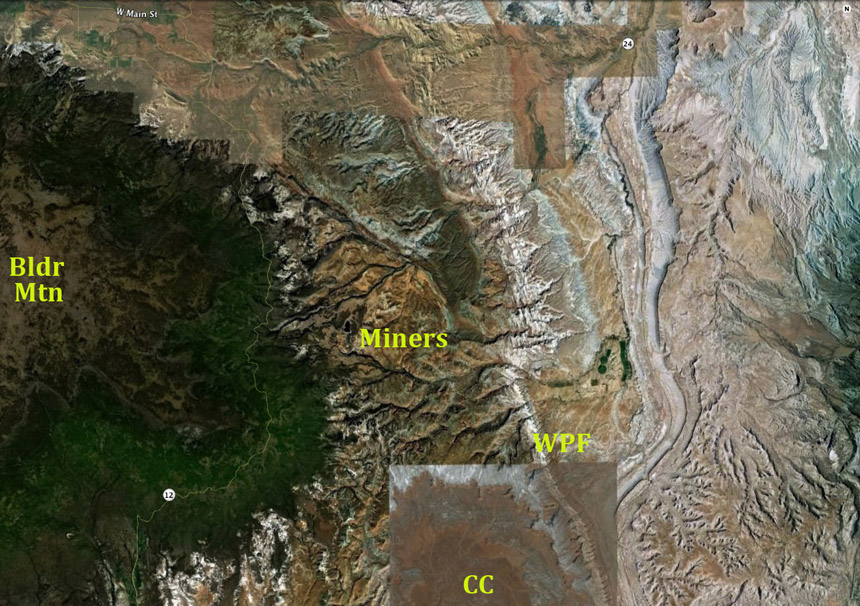

Above, in Google Earth satellite imagery, Boulder Mountain is the highest point and easternmost extension of the Aquarius Plateau, a massive Colorado Plateau remnant that displays largely horizontal sedimentary levels near sea level running from Paleozoic through Cretaceous times, then (after a period characterized by an extensive fresh-water lake) was extensively capped by Cenozoic (Oligocene and later) volcanic lava flows that formed the vast Marysville Volcanic Field (note the pale flat-top color at far left). These hard volcanic layers have protected this plateau edge from the erosion that has stripped away much of the land to the east. Click on the image to enlarge it.

This high-elevation plateau (maximum elevation = 11,319 feet); mean elevation of mountain top = 10,836 feet), hosted a true ice cap with several outlet glaciers during the Last Glacial Maximum (26,000-19,000 years ago). Glacial Scouring and the heavy stream outwash sent down black boulders across the Fremont River valley and other drainages, eventually giving the mountain and its nearby town their names. On the image above you can make out the faint line of Highway 12, which runs along the flanks over mostly Quaternary alluvium produced during and after that time.

The map at left shows the northwestern portion of the Colorado Plateau, which is distinguished as the High Plateaus section, characterized by high, north-trending plateaus, separated from each other by major faults and grabens. The western portion straddles both Plateau and Basin-Range, marking a transition between the two. The map (adapted from Rowley et al 2002) also shows in faint pink most of the vast Marysville Volcanic Field, of which the Boulder Mountain volcanic top is a part. Boulder Mountain is located on the map as the pink protrusion at far lower right of the Aquarius Plateau portion. For a full view of the Field, click on the map to enlarge it.

The distribution of these volcanics indicate they were laid down before the dissection of the plateaus, in several episodes, and at much lower elevation than they presently boast. On the Fish Lake plateau north of our immediate area they reach thickness of more than 2,000 feet, composed of both massive lava flows and pyroclastic ash flows.

Moreover, the entire sequence of igneous deposits were spread on top of lower Cenozoic (Paleocene to lower Oligocene, ma) fluvial and lacustrine sedimentary rocks, which in turn overlaid layers of Cretaceous sediments that were mostly marine. Until near the end of the Cretaceous Period, these locations were near or below sea level. Now they reach elevations of more than 11,000 feet.

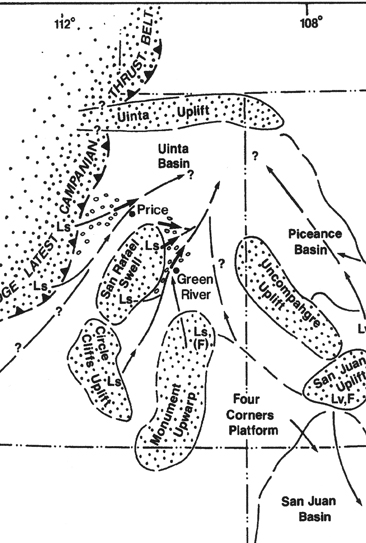

Apparently most geologists now agree that the earliest raising of the Plateau from its near sea level position began toward the close of the Cretaceous with the rise of the Sevier Orogeny to the west of the Hingeline (see "Campanian Thrust Belt" at right), and then the Laramide Orogeny east of the Plateau. These 80-50 mya compressions produced mountains to the west and east of the Plateau, but also, some somewhat later, the several more local uplifts we have already seen present in the region. However, the sequence of the High Plateaus also tells us that these early Plateau uplifts (San Rafael Swell, Circle Cliffs, Monument Uplift, et al) remained during that time at fairly low elevations, and were blanketed by sedimentary formations that appeared during and even after their rise. The map at right shows erosion flows from the mountains raised by the "latest Campanian Thrust", with subsidiary flows from the contemporary uplifts with which we are all now somewhat familiar, which during and after the end of the Cretaceous raised sediments in the basins to the east and north,

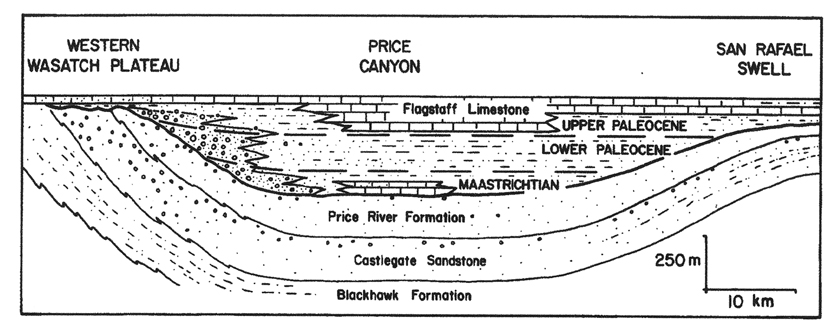

The widespread presence of a later, mainly freshwater-lacustrine Lake Flagstaff during the Upper Paleocene in this area shows that by that time (58-55 mya), both Plateaus and uplifts had become flattened out beneath yet another sedimentary layer. The image below shows both the San Rafael Swell and the Western Wasatch Plateau (as well as basins in between) lying below the Flagstaff Formation, relic of a lake whose size remains a question for geologists (some reports show it running from East-Central Utah all the way to its southwestern corner) but which definitely existed near the Circle Cliffs of our area (forming a sedimentary layer in Boulder Mountain strata):

The curvature of the underlying late-Cretaceous deposits (Price River, Castlegate, Blackhawk, all Upper Cretaceous members of the Mesaverde Formation, 80-60 mya) show that they predated the rise of the Plateau and San Rafael Swells. Both the Boulder Mountain volcanics and the Henry Mountain Intrusions come afterward, and are associated with a second major uplift, occurring in the middle Cenozoic (Oligocene and lower Miocene, 32-22 mya), corresponding to the intrusive laccoliths of the Henry Mountains and elsewhere in our region. But a third major uplift has apparently occurred as well, and some geologists claim this one has raised the Plateau much more than the previous two. For example, a recent paper by Sahagian et al (2002) bases an estimate of the timing of the overall Colorado Plateau uplift on "a technique for measuring paleoelevation on the basis of the vesicularity of basaltic lava flows." Setting aside the specifics of the technique and details of measurement, I merely observe their findings: a slow uplift (some 40 meters per million years) began at least 25 mya, but this gradually accelerated to 220 meters per million years in the past 5 million years. (Geology Sep 2002, v. 30, no. 9, pp. 807-10).

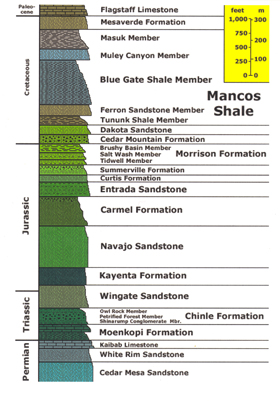

Bearing all this in mind, we continue our travels below along the flanks of Boulder Mountain on Hwy 12, here looking back toward the Northeast toward the southwestern flanks of the San Rafael Swell. In the middle foreground are more tetons of the Navajo Formation, which outcrops along the lower flanks of the mountain here and there, and beyond that lies the northern end of Miners Mountain. This mountain complex, deeply eroded from the Jurassic formations around its flanks into Triassic and even Paleozozoic layers (including the Kaibab Formation, topmost Permian layer at the Grand Canyon), forms a substantial uplift lens that is connected with the Circle Cliffs, but is set apart from it in the geological sources I have consulted, and clearly its erosional history is quite different.

Below, another near view of a portion of Miners Mountain, deeply dissected here and beyond which in middle distance lies the cliffs of Navajo Sandstone near the "Golden Throne" portion of the Reef, capped with the reddish Carmel Formation. Beyond that, beyond the depths of the Waterpocket Fold, lie the mesas of the Blue Hills, which flank the Route 24 entrance to the Park, including at left-center Factory Butte, part of the Mancos Shale formed from marine sediments deposited in the Western Interior Seaway during the Late Cretaceous period (90-80ma). The top of the Butte is composed of the resistant Emery sandstone (85-83ma), overlying the Blue Gate shale (90-85ma) which forms the stark bluish badlands that line much of the highway west of Hanksville. Here we look directly beyond the Reef at remnants of Cretaceous seas.

Below, we look across the southern portion of Miners Mountain toward the mass of Hentry Mountains laccoliths spread across the horizon. The Bown Reservoir at right center, situated on alluvium dating from glacial times, is non-natural, but is only one of many lakes located along the flanks as well as the top of Boulder Mountain (a total of about 80 small lakes). At middle left lies part of the heart of Miners Mountain uplift.

Below, another Google Earth satellite view from above Boulder Mountain, here looking out eastward toward the northernmost laccolith of the Henry Mountains. At lower to middle left, beyond the forested edge of Boulder Mountain and its Highway 12, you see a central part of the Miner Mountain Uplift, which down-dips into the white line of the Waterpocket Fold running laterally somewhat above left-center. You can see how deeply stream erosions have cut into this formation. At far right, you see the northern end of the Circle Cliffs Uplift, which presents a very different aspect to the viewer. From this perspective it looks more like a basin (with its encircling higher cliffs) than an uplift.

As we drove toward the downslope of the mountain that leads to Boulder Town, out to our left we look below southward across the southern stretch of the circle cliffs edge (at upper middle-left, while the more whitish peaks in nearer foreground and toward the far right are mostly Navajo Formation on the mountain's flanks, part of the near-remnant of the Circle Cliffs on this western side). Far beyond, stretching all the way across the horizon are the Straight Cliffs of the Kaiparowitz Plateau.

Below, our Google (3-D) satellite image now hovers over Boulder Town at the base of the mountain (visible at lower left near the Highway 12 icon), looking Eastward into the Circle Cliffs. While the Highway's traverse runs along the bottom of the image toward the memorable cliff-edged road we saw in a video clip earlier, here we turn eastward on the Burr Trail to enter the Circle Cliffs Uplift. In this image, Navajo Formation Sandstone is visible on the edge of the Circle Cliffs Uplift in and about Boulder Town, while the main body of the Uplift comprises the orange-yellow and reddish formations further east. Note that in part this color difference is an artifact of Satellite photography, but in part color differences do reflect difference in the formations exposed.

Boulder Town lies in a small, water-blessed valley at the mountain foot, draining into the Escalante River. Its beauty is enhanced by the massive Navajo Formation sandstones that rise around it, as this remarkable one below at the beginning of the Burr Trail. Click on the image for a close-up view of the strange pillowy-appearing edge shown at the right, the cause of which I have not been able to determine.

From this point, we enter the Burr Trail, onetime pathway of the film-famous Butch Cassidy and Sundance Kid, and geological zone of considerable contemporary interest and pleasure.

Click on the image at left to enlarge it!

Go to:

3b. Burr Trail and the Circle Cliffs Uplift Zone

3c. Waterpocket Fold to Notom

3d. Beyond the Waterpocket

or, go to other locales:

Return to Part One: Introduction

Go to Part Two: From Blanding to Capitol Reef