3c. Waterpocket Fold to Notom

Above, from a viewpoint standing on Kayenta Formation and looking through a gap in the Navajo toward the northeast, we see a wide, much lower valley cutting across our view (which passes a watercourse running into the valley from a portion of the the sunlit Henry Basin beyond. Note how the massive cliffs facing us display sloping gray cliffs, topped by a distinctly different and harder capstone layer. Click on the image to enlarge it.

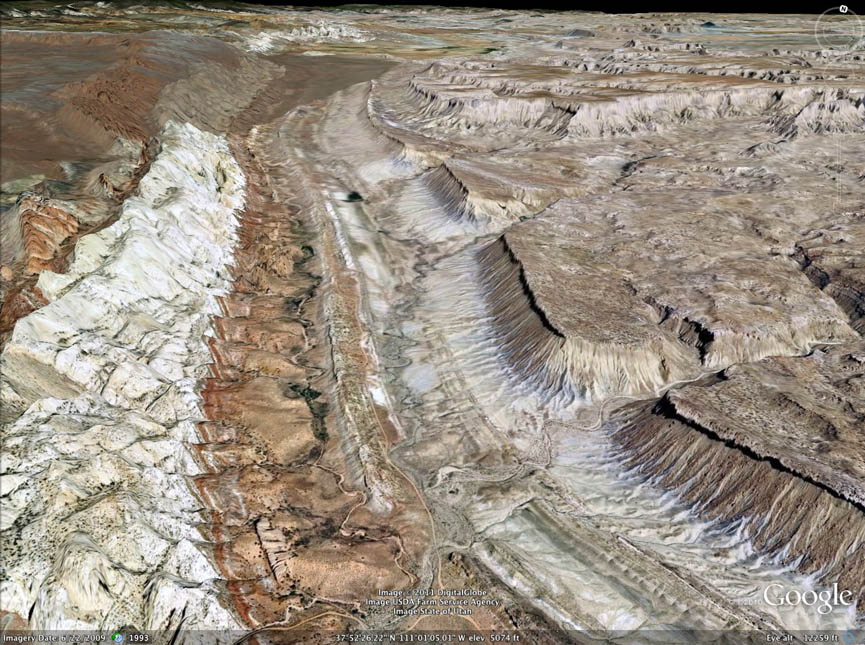

Below, looking north thanks to Google Earth from a point somewhat south of (and much higher above) our vantage point above, we see the ending strip of the Burr Trail road where it enters the Waterpocket Fold at lower central image. This wide valley of the Fold is called Hall's Valley, and the (intermittent) stream running through it is Hall's Creek (which drains south into Lake Powell). The east side of the Fold here is marked by what proves to be an extensive line of massive cliffs beyond the wide if rather rough trough that here curves toward the northwest. From this (1.3 exaggerated) 3-d satellite view, these grayish cliffs appear to have overhangs, an artifact of their caprocks having a more vertical surface than the slopes below. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, our Google aerial view now looks toward the north-northwest, giving us a straight-line view up Hall's (Waterpocket) Valley. Note how the line of Gray Cliffs appears to pinch out in the distance, and note also the contrast between their obviously somehwat west-upward tilt and the absence of tilt in the roughly parallel line of cliffs further to the east on the Henry basin bench now more visible to us. Click on the image to enlarge it.

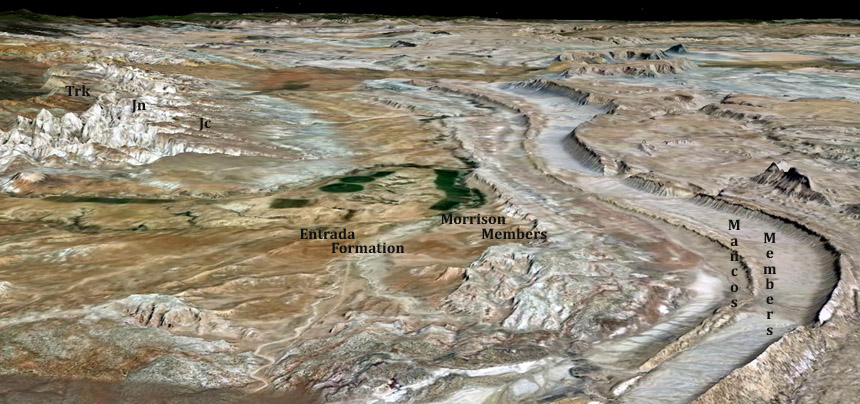

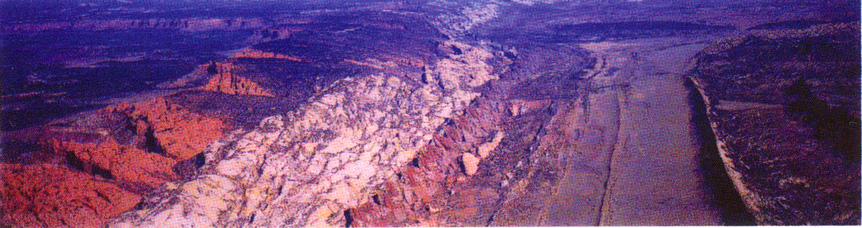

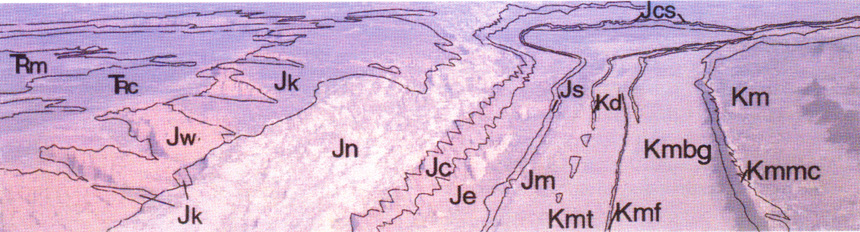

The value of these somewhat exaggerated 3-d Google images becomes clearer when we recall that the geologists are avowedly here to help us understand what we are seeing. [Thanks to Morris et al 2003, p. 85 for the three images below, which considerably clarify matters.] Below is an aerial image taken without artificial 3-d exaggeration from an airplane, presumably by a geologist. Several features of this image are striking, aside from the poor quality of its color representation. First, Note how the steepness of the strata folding, which is very sharp along image center, flattens out in the Kayenta at left (which expands out away from the very-steeply-set Navajo) and the reddish Wingate that underlies it. Second, observe the realistic view the image gives us of the far-upper-left Circle Cliffs depression status: as Steed put it, definitely a "breached anticline", with a depression in its very middle below its still-uptilting rims. We can even see hints of the "inner escarpment" that marks the edge of the Chinle Formation, below which lies the Moenkopi. Third, the red-tipped Carmel Formation running up the middle of the image appears here to rise above and shadow the Navajo. This as we will see is partly an artifact of the angle of lighting, but partly also real, we just didn't get a chance to see it very well. Fourth, see how flat and broad the Fold Valley appears in this image, so thata few geological features stand out clearly. The flatness reflects the relative softness of the geological strata at those locations.

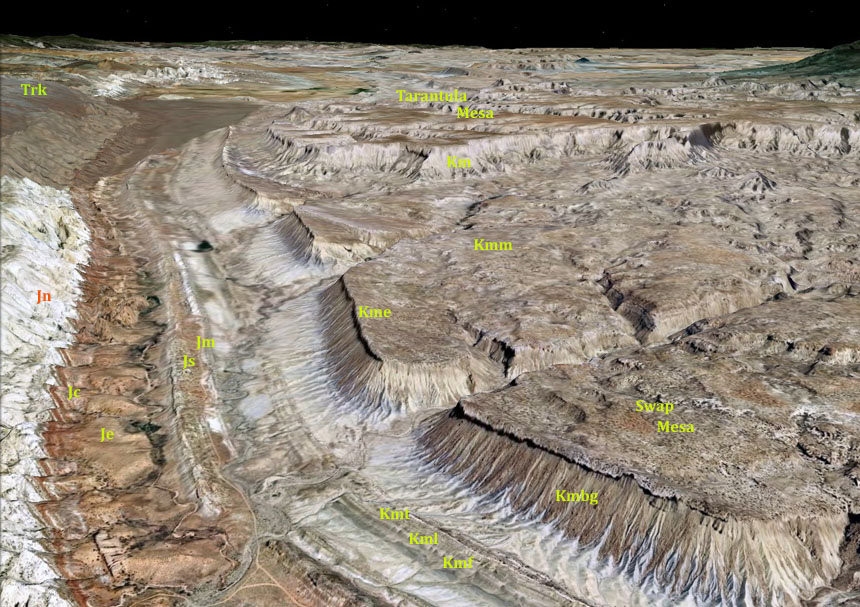

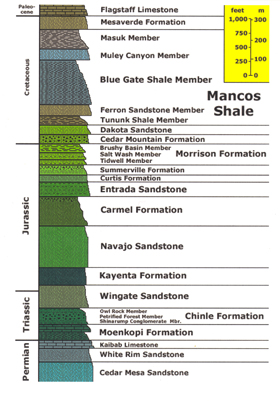

Below, we see the accompanying identification markers of the formations involved. This is useful for our subsequent travel up the fold. TRm at far left is the older Triassic Moenkopi, TRc the Chinle, Jw the Wingate, Jk the Kayenta, Jn the Navajo. Jc is the Carmel, but we may note here that from the ground the Carmel will look to us much less striking than it appears in this image, where the Carmel is rising over and shadowing the immediately adjacent Navajo. (That is because our roadway view was restricted all along this part of the course.)

Further to the right, Je is the Entrada Sandstone of the Middle Jurassic which has a much flatter aspect than the Carmel, and then a lower ridge of Js, the Summerville Member of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, then the Morrison (Jm) undifferentiated. The low-lying flats further right are all Cretaceous in age, and (except for the lower Dakota Formation (Kd), Members of the Mancos Formation: Kmt, Tununk; Kmf, Ferron; Kmbg, Blue Gate Shale; Kmm, Masuk Shale; and Km, undifferentiated Mancos.

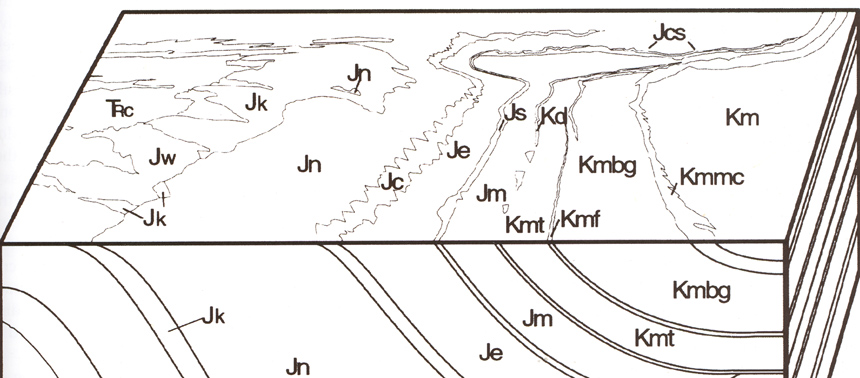

Below, our geologists provide a visual estimate of the relative strike and dip of the various strata of the Fold, which in turn gives us a sense of the immensity of the original Uplift as it emerged some 60-50 million years ago.

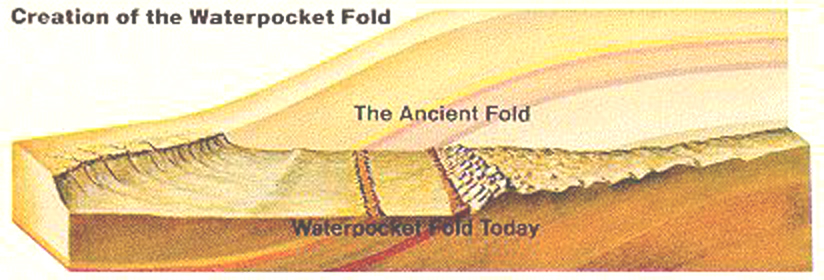

Below, an imaginative depiction of the amount of real estate involved, here shown with east on the left and west on the right. This imagines the uplift occurring in the absence of coeval erosion, which of course never happened, but amounts of erosion debris approximating that volume did indeed flow downstream toward the seas. One of the interesting questions is exactly when what relative amounts of this huge mass were removed: during initial uplift, during the great Miocene Orogeny, during the 15ma period of Basin-Range extension, during the last 5 million years when uplift definitely accelerated?

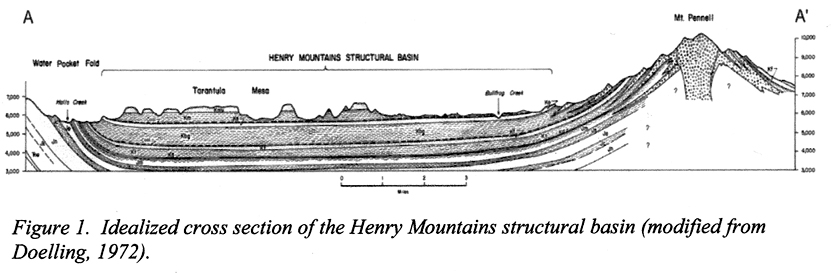

Below, yet another diagram cross-section of the Waterpocket Fold, now with west on the left and east on the right (as we have become more accustomed). This geological map (copied from a paper by David Tabet on the coal resources of the Henry Basin, see that link to scroll to a better image) returns us to matters of the Henry Basin (we opened the subject in Part 2, Blanding to Capitol Reef). This diagram shows a much more realistic model of the geology than we saw in Part 2, but unfortunately my copying skills and technology did not provide a fully legible result (even with enlargement, hence I don't provide one here).

However, it does give us a good sense of the extent of this basin, a fairly symmetrical syncline which contains enough coal to warrant the author's detailed study promoting the prospects of mining coal contained in some of these strata. Note the view of Tarantula Mesa toward the west, where the late Cretaceous Mesaverde Formation provides a hard cap over softer Mancos. Underlying strata are preserved in this basin much as they were laid down and two of the Cretaceous Mancos Shale Members have significant coal deposits. This western Henry Basin extends northward well into the Blue Cliffs Badlands northeast of Caineville.

Below, again a Google Earth image that includes identification labels for the Formations and Members we can see. Both Tarantula Mesa and Swap Mesa are objects of attention for coal mining. The latter on the lower-right quadrant of the image, exposes Mancos Masuk Shale (Kmm) on the main mesa but is capped with harder Mancos Emery Sandstone (Kme). Below, the exposed sloping layers are Bluegate Shale Member of the Mancos (Kmbg).

On the right side of the flats (toward the left of the image), older Members of Cretaceous Mancos are exposed. On the left side of the flat, we can see the Notom-Bullfrog Road running along the junction between the Summerville Member of the Jurassic Morrison and two of its later Members. Near the Reef's continuous base where the Carmel Formation rises against the Navajo, the earlier Jurassic Entrada Formation displays small, relatively flat mini-mesas (Je).

So below we began our drive northward (note the roadmap-image above at bottom toward the left). We ride here alongside a steep- rising escarpment of lower Morrison Formation, Summerville Member, composed of thin beds of reddish-brown siltstone and mudstone that underly the main body of the Morrison. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, we look back southward having passed this long line of the Summerville, which pinches out somewhat at this point, and we also observe behind it a rising of the later main body of Morrison (Salt Wash and Brushy Basin Members). (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

As the Summerville declines in elevation, we are now able to look westward (and upward!) at the immense body of Navajo Formation, with the "flatirons" of the older Carmel Formation flanking it in brown and red. Click on the image to enlarge it. Flatirons are triangular spurs/ridges having a narrow apex and broader base, typically a plate of steeply inclined resistant rock between deep valleys produced by erosion.

Continuing northward, below we now see a more extensive view of the main elevations of the Reef, with Navajo rising far aboveand the Carmel Formation flatirons jutting out lower down. Directly in front of us the Summerville Morrison forms a jagged hogback, while the main body of the Morrison shows its red-and gray slopes at far right. The Carmel Formation flatirons are very striking here, and it's clear that they do rise a bit above the Navajo in some places. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, now we run between the Summerville and main Morrison body, with the reef continuing northward as far as our vision allows. (Click on the image to enlarge it.) (You may guess here, correctly, that we were thinking rain along this Bentonite-rich road.)

Below, when we emerge out into full confrontation with the Navajo, I find it hard not to feel overwhelmed by a kind of awe. The sense of time, sheer mass, and vast distance make comprehension difficult. George H. Davis of the Department of Geosciences at the University of Arizona has made a study (1999) of the deformation bands distributed through this sandstone, showing it displays great varieties of deformation: in geographic orientation, in vertical/horizontal direction, in macroscopic to microscopic structures, and in the types of faulting, compression, and extension involved in different times and locations. Click on the image to enlarge it.

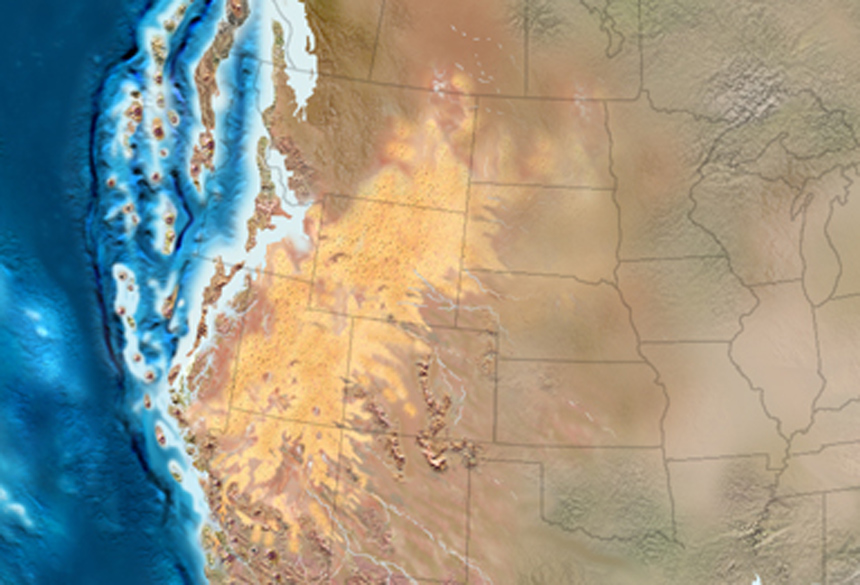

The expanse of this incomparable sand-sea or erg over western North America must also be borne in mind. Below is the recent estimate by Ron Blakely et al of its reach in the early Jurassic 180 million years ago:

Below, looking back to the south along the reef, we can readily comprehend how the early European travelers in the area, coming in their Conestoga Wagons (they called them "ships of the desert"), would have, like sailors of the time, considered this massif a formidable "reef" indeed. Click on the image to enlarge it.

As you can see in the image above, the valley opens out as we proceed to the north. Further on, we rose up onto a bench of the early Jurassic Entrada Formation, looking backward toward the main line of the Reef with its dominant Navajo face on the west and the Mancos Shale cliff to the east. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

From this bench, then, we could look northwest toward the central part of the National Park: the Golden Dome and its associate Navajo Formation monoliths, and the highest rise of the kayenta-Wingate escarpment, here long since largely stripped of its ancient Navajo carpet. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

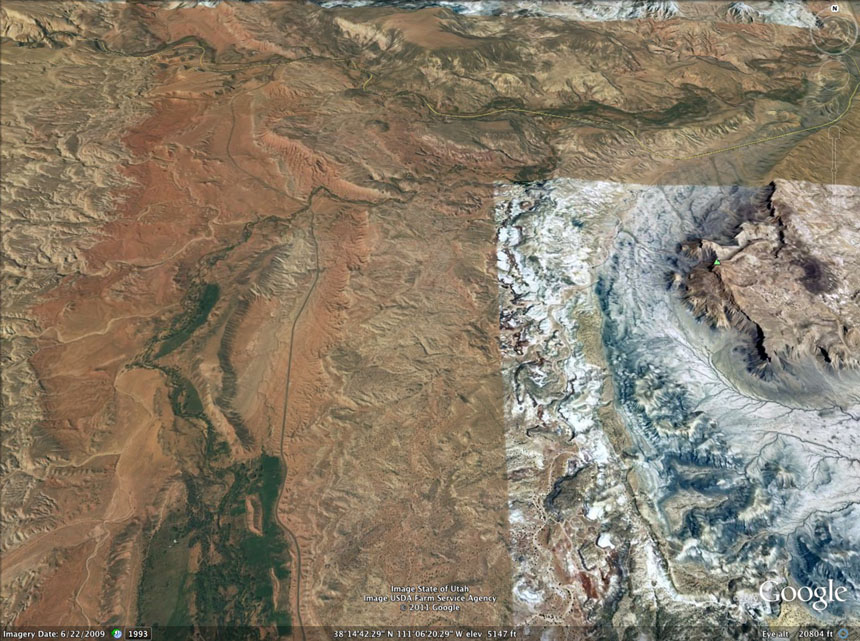

Below, a Google Earth image now looking down toward our vantage point for the previous two images: the bench marked "Entrada formation." At middle far left, Sandy Creek runs left to right out of the northern portion of the Uplift, providing water for a strecth of irrigation farming at image-center before it continues north to its confluence with Fremont River in the upper middle distance.

Continuing northward, we rise for a time and below look back along Sandy Creek, which parallels Morrison Formation Members (with the higher Cretaceous Mancos Shales behind these, and a Henry Mountains sentry looming beyond). Click on the image to enlarge it.

From this perspective, below (and our zoom lens) we can see how high the Mancos Shale cliffs rise above the Morrison at this location. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Below, we look over Sandy Farms for a final view of the center of Capitol Reef National Park rising toward the northwest, where Carmel Formation still blankets the Navajo. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

Below, we continued on the Notom Road northward from the Sandy Creek farming area (you can see here where the stream turns northeastward to flows into Fremont River near the top), but then we turned off onto the Old Notom Road which also runs northeastward, aiming to visit another agate location (dictated, again, by our Rockhound book). If you Click on the image for a close-up view, you will be able to see the Old Notom Road as well as the location in the Morrison Formation where the red-and-white Bentonitic deposits reappear, looking nearly identical to those we saw near Hanksville. On the map you see below, this Formation lies in the photographically distinct portion of the image that is very whitish, but along the flank to the left of the paralleling one with the more bluish cast. This latter is Cretaceous Mancos Shale, and (with its higher cliffside Members at far right), swings around to the northeast here to form what is called the Caineville Reef.

Below, the agate location, not far from Highway 24. You can see its similarities to our Hanksville location. This route was also appropriate because it brought us, not near the central Capitol Reef Park centers (where we should have been scheduled to stay had we used better pre-trip foresight), but closer to Mexican Hat, Utah, quite a long distance to the south but where reserved accommodations awaited us.

Click on the image at left to enlarge it!

Go To:

4. Beyond the Waterpocket: Cedar Mesa, Mexican Hat, Monument Valley et al.

Back to (3) and Various Capitol Reefings

Back to (2) from Blanding to the Reef

Back to (1), Introduction to the Geological Context