The Agaves and Nolinas

(Click on each of the images above to enlarge it.)

Main sources: Castetter, Edward et al, 1938, The Early Utilization and Distribution of Agave in the American Southwest, University of New Mexico Bulletin 335:Biological Series vol;. 5 No. 4; Dimmitt, Mark, "Agavaceae and Nolinaceae", in Steven Phillips and Patricia Comus, eds., 2000, A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert, pp. 155-164, Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Press, Tucson; Epple, Ann, 1995, A Field Guide to the Plants of Arizona, pp. 157-8, Lew Anne Publishing Co., Mesa AZ; Bowers, Janice, 1993, Shrubs and Trees of the Southwest Deserts, Tucson: Southwest Parks and Monuments Association; Hodgson, Wendy, 2001, Food Plants of the Sonoran Desert, Tucson: University of Arizona press, pp. 13-45

The Agaves, Yuccas, Sotol, Beargrass, and other related plants were once grouped together as members of the Lily Family (Liliaceae), but more recently botanists have split this very large grouping apart, and taxonomic relations among the members is controversial. We will simply treat these four types separately under the general heading above. (For discussion of these plants in relation to our Biomes, see San Pedro Valley Flora Today.

Agaves (Agavaceae):

Agaves are purely New World plants in origin (though since the 1500s C.E. humans have now spread them much more widely around the world), ranging in size from the tiny mescalito (the size of an apple) to the Mexican giant maguey which may weigh over a ton. All Agaves have rather thick, succulent leaves that form rosettes, and most are stemless so they tend to form rather tight clusters. Leaves vary widely in color and size, but leaf edges are usually lined with numerous sharp spines and each leaf is tipped with a single sharp spine. Flowers emerge on a single vertical stalk that grows out of the center of the rosette (and to which the name "agave" alludes), and most species bloom only once and then die (anywhere from 3 to 50 years depending on species). But most Agaves actually multiply mainly by means of underground suckers.

In the Southwest, Agaves are plants of the foothills and lower mountains rather than valley floors. In our area, the main species are Agave palmeri and Agave Schottii:

Agave schottii, or "Shindagger",

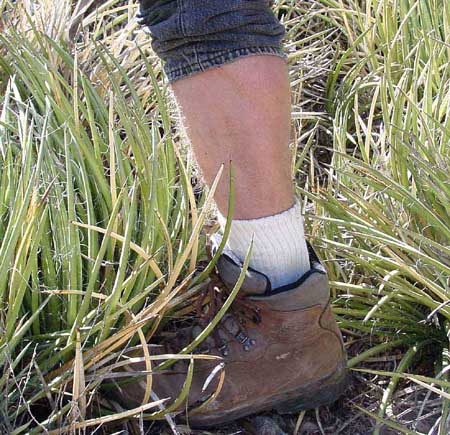

is also called "Lechuguilla" by some folks in our area (though Agave Lechuguilla proper is an endemic plant of the Chihuahuan Desert and limited to New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico). Our shindagger is found south of the Gila River in southeastern Arizona, in foothills and lower mountains at elevations of 4,000 to more than 5,000 feet, where its short, stiff, spine-pointed leaves (which unlike most agaves lack edge-spines) often form a veritable carpet on dry rocky slopes. Below is a small continuous stand of it in Sierra Blanca Spring Wash photographed in February 2004:

Shindaggers respond to drought quickly by drying up. Below, a mini-forest of it located at Old Hunters Camp (with a single ocotillo contesting the growing space), had become severely dessicated at the culmination of our 2002 drought:

Cattle (not to mention people) shy away from walking in thick stands of it, so it often supports grasses which otherwise might be overgrazed. One can more fully appreciate this in relation to the image at left. (These Shindaggers, encountered in February 2004, have responded to good rains.)

Shindagger is the "amole" of Arizona, where in former times it was a very important source of soap for the O'odham and other Native Americans. (It produces a strong lather when mixed in water.)

While they present a somewhat baleful prospect to hikers, shindaggers produce very beautiful flowers when fully in bloom. A short walk east from Old Hunters Camp, at the base of Sierra Blanca, in June 1995 we captured a field of blooms with our old video camera (the last time we saw such a display):

At left, shindaggers at the same location near Hunters Camp sprang into beginning bloom following the late rains of August-September 2002;

Below, in full flower at the same location, June 1995.

Agave palmeri

This Agave, common in foothills of 3,300 to 4,000 feet in our area, lives in an area extending from the Baboquivari Mountains in the west to New Mexico in the east, and from the Gila River in the north into the Sierra Madre Occidental to the south.

The photographs below show a feature that distinguishes most agaves from the yuccas or the (African) aloes -- sharp, stiff spines distributed along the sides of the leaves as well as a single needle-point at the tip. (Leaf color is rather variable in this beautiful plant.) (Click on each image to enlarge it.)

.

.

Below, more than 20 distinct Agave Palmeri plants are blooming on this hillside near Sierra Blanca in August of 2001:

At left, Agave blooms on the Ridge Road, July 2003 (Click on this image for a closeup):

Note that its sibling is not blooming, and retains its full color, while the bloomer of the pair is dying down at its base.

Below, blooms detailed (Click on the image to enlarge it)

As the fruit ripens, the whole plant begins to die at the base. Typically it turns a reddish color at first, as shown below in October 2005.

Agaves were extensively used by the O'odham and Apaches for food, drink and fiber. See Castetter, et al and Hodgson (cited above), for detailed discussions of the labor-intensive processes entailed, for example, in processing the base of the fruiting stalk into strong drink. We describe a very important agave in this Native American tradition below.

Agave Murpheyi

also known as "Hohokam Agave" because it was cultivated by pre-Columbian Hohokam people in our area, and continues to be cultivated by the O'odham in southern Arizona. We have not seen Hohokam Agaves on our lands (climatic conditions may not be favorable for them at this time), but we're discussing potential efforts to cultivate it. See the link below for more information on this plant.

Hohokam Agave

(Specimens of these may be seen at the Desert Botanical Garden, Phoenix, Az)

The Nolinas

Yuccas, Sotol, Beargrass

Compared with agaves, Yuccas have thinner, straighter, less succulent leaves, and many of them grow substantial trunks. Also unlike agaves, most of them bloom multiple times, and their flowers are distinctive -- large, bell-shaped, and white. The two species native to our area are

Yucca baccata

"Banana Yucca" (above) is very drought-tolerant and cold-hardy; it is found from Colorado/Utah to Mexico (in our area, from 2,000-7,000 feet). Its leaves are thicker and stiffer than Yucca elata, and it has a typically much lower profile. Most of the plants in our area have short, creeping stems, though stems do occasionally attain some height (see above, the plant toward the right).

Orioles (and other birds) favor the fine-stringy leaf-edges for weaving their nests -- see the image at left. These are strong and supple fibers.

In May of 1999, we sat beneath the great sycamore tree at Coati Terrace in Hot Springs Canyon, watching a pair of Orioles weaving their nest directly overhead. Each one would fly across the canyon to the base of the Red Trail, where a stand of Yucca baccata provided them with raw materials.

Below, an old Oriole nest stood firm at Sierra Blanca Spring in February of 1996:

This yucca blooms from April to June, and will bloom many times in its lifetime, depending on rainfall. Below left: a blossom in May of 2003. Below right: April 2004, flowers opening along Pool Wash Ridge Road: (Click on each image to enlarge it)

..

..

Below left, Y. baccata flowers in early April, 2004 (click on the image for a close-up of one flower): Below right: two "bananas" have formed by May 2004:

.

.

The fruits of Yucca baccata contain considerable sugars, and they are eaten by many types of mammals. Native peoples considered it an important staple. According to Hodgson (cited above, p. 45), "Native peoples sometimes gathered the immature fruits to ripen in the sun" because otherwise birds, deer, insects, etc. would demolish them, but the immature fruits as they stand "are extremely bitter and have a long-lasting aftertaste." When fully ripened in August through October, they are "pleasant-tasting, sweet, and nutritious." However, be warned: they are also a strong laxative.

Yucca elata

This species, called "Soaptree Yucca", needs more water than Yucca baccata, but is also very cold-hardy. Its trunk grows higher than Yucca baccata, and its leaves look more like bear-grass.

According to Dimmit (op.cit., p162), the "Soaptree Yucca" is found mainly in Desert Grasslands "from central Arizona to west Texas and northern Mexico" and its range extends into the "upper margin of Arizona Uplands, from 1,500 to 6,000'". In our general area, very large numbers may be seen growing alongside Interstate 10 on the highest San Pedro River terraces overlooking Benson on the west side, then toward our area on terraces north of Benson (the location of the photo above, taken in June 2007, on a Tres Alamos terrace), and along the Cascabel Road in the river floodplain all the way to Cascabel. However, Yucca elata becomes quite rare in our Saguaro Juniper uplands above the floodplain of Lower Hot Springs Canyon, presumably because of water limitations.

We have seen a few Y. elata in our uplands mainly near Saguaro-Juniper Hill, and they are also present in the Red Tank Wash among the Junipers there, but they are more common in the lower sandy washes of the Soza Mesa drainage near the elevation of the San Pedro River floodplain -- see the image at left for a pair of very old ones observed there. (Click on the image to enlarge it).

We have seen a few Y. elata in our uplands mainly near Saguaro-Juniper Hill, and they are also present in the Red Tank Wash among the Junipers there, but they are more common in the lower sandy washes of the Soza Mesa drainage near the elevation of the San Pedro River floodplain -- see the image at left for a pair of very old ones observed there. (Click on the image to enlarge it).

The image below, taken northeast of S-J Hill in October 2002, shows a clustered fellowship of Soaptree Yuccas at left-central, with their long stems (often branched), and the remains of tall flower stalks. At lower right in the photo is a stand of Y. baccata. Above this elevation in these uplands, we see only the latter.

From a distance young Y. elata look like Sotol plants (see further below), but their leaves lack the sawtooth edges (below right).

...

...

Yucca elata was used by Native Americans for soap, and its leaf-fibers for making sandals, mats, baskets and nets. Today, orioles strip the strong whitish fibers that curl off the blades (see below left) and use them to weave their nests. When fresh, the white flowers of Y. elata, below right, are delicious in salads and contain much Vitamin C (Click on each image to enlarge it).

..

..

Sotol (Dasylirion wheeleri)

Also called "Desert Spoon", although long classified as a member of the Agave family, this plant looks from a distance rather like Yucca elata (see essay on the latter above), until one examines the leaves at close range --

-- and sees that each leaf has numerous, mostly upward-pointing saw-teeth on each edge, unlike Yuccas but characteristic of most types of Agave.

The name "Desert Spoon" derives from the distinctive shape of the enlarged bases of these leaves, which clasp the stem in densely overlapping spirals, producing the leaf-rosette patterns so typical of Agaves (Bowers, cited above p. 33). Some of the "spoons" may be seen below left, scattered along the edge of the Red Tank Wash after a rain, after hungry Javelinas had demolished most of the mother plant (at left-center in the photo), which had previously died. Below right, a close view of an array of "spoons" remaining after those above have been removed.

.

.

Sotol grows mainly on rocky hillsides between 3,000 to 6,000 feet, and is primarily a plant of the "Desert Grasslands" or "Apachean Savannah" rather than desert proper. In our area we see it mainly on north-facing slopes or (as above left) along washes.

It flowers once every several years, sending up a stalk in May 2004 (below left), each plant's tall, densely-branched inflorescence eventually bearing thousands of small whitish flowers. Below center, a close view of a seeding stalk in September 2007. Below right, old stalks remain on surviving plants in November of 2002 in Upper Hot Springs Canyon. Unlike Agaves, Sotol does not die after a single flowering. (Click on each image to enlarge it.)

.

. .

.

In former times, Sotol was used by Native Americans for manufacturing sleeping mats, enclosure mats, baskets, thatch, and rope, and its immature flowering stalks were boiled and eaten, or made into an alcoholic drink.

Beargrass (Nolina microcarpa)

Beargrass is not a grass at all: like Sotol, it has sharp teeth along the edges of its leaves --but in this case, the teeth are very fine, almost microscopic), and like Sotol, Yuccas, and the Agaves, its leaf bases clasp its stem in densely overlapping spirals that produce leaf-rosettes. As Janice Bowers (cited above, p. 39) says, Beargrass rosettes "make dense, fountainlike clumps on hillsides and canyon slopes at the upper margin of the desert".

We see this Nolina in very few locations on our lands. The solitary plant shown above is located in the wash below the Red Tank (where many very old Juniper trees are also found). One other location, where we see a number of these plants, is a north-facing slope in the narrowness of Upper Cottonwood Seep Canyon, photographed in March 2002. Here, below, several Beargrass clumps flank the single Sotol plant residing at center-right, all located under a spreading Mesquite tree.

Like our Juniper trees, Beargrass in our area appears to be a remnant from earlier, wetter times.

Below, a beargrass clump in full bloom in August 2003. At center, a single blooming stalk; at right, clusters of creamy white flowers. These bud stalks were eaten by native Americans.

.

. .

.

The long-fibered, rasp-like leaves of Beargrass have traditionally been prized by the O'odham as materials for constructing their beautiful baskets (of all sizes) -- Beargrass is used for the interior coil structure of the baskets, and they also use it for making brooms. They also place mats of it as a cushion in earth ovens for steaming Agave hearts. Below, see the mass of leaves sprouting from the base

Then see below for a closeup of the concave (inner) side -- the tiny edge-teeth are here barely visible:

Here, below, is a revealing contrast between the two Nolinas, Sotol and Beargrass: taken in Lower Cottonwood Seep Wash on a north-facing slope in January 2005, in this shows Sotol are the more bluish-toned plants, while the similarly-shaped Beargrass clumps have a more yellowish-to-greenish color cast.

Back to Our Lands and Their Creatures